Whirling Disease

Introduction

Whirling Disease’s spore-worm-trout cycle now a challenge for New Mexico fisheries

by Marti Niman

It seems an unlikely place for an epidemic-a remote steppe spattered with a blaze of wildflowers, the sky reaching for a rim of earth. Three lone figures stretch a series of nets across a pond, the white buoys arching dotted lines across the dark water. It’s a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy or some romantic 19th century novel, but this bucolic scene is grounded in modern science and grim foreboding.

The lone figures are cold-water fisheries biologist Steve Bates, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, and New Mexico State University co-op students Lori Curry and Jennifer Lowder. They are trying to capture trout recently stocked in a private pond to test for the presence of whirling disease. The name sounds like comic relief, but whirling disease can gut fish populations and there is no known effective treatment. Rainbow trout are particularly susceptible and other varieties of salmonids differ in degrees of resistance.

Fish Head Stew

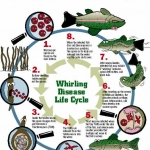

The disease is not caused by a virus, but a single-celled parasite with the tongue-spinning title of Myxobolus cerebralis. Its life cycle waltzes between two hosts: trout and the bottom-dwelling tubifex worm. A changeling microspore that alters form in each host, the disease can turn young trout into horror show aliens with blackened tails, bulging eyes and deformed humps by feeding on cartilage near their heads. The resulting damage to the nervous system and skeletal integrity launches young fish into a kind of permanent spin cycle that gives the disease its name. Fingerlings are particularly vulnerable to heavy infestations, since their soft cartilage has not yet hardened into bone. While adult fish are not visibly affected, they often serve as spore carriers. Nonetheless, infected fish are edible and pose no health hazard to humans.

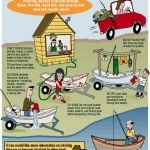

The microspores hitch rides on birds, bears, boats, wading boots or just about anything that moves from one body of water to another. They surf downstream, explode into the water when infected fish die, or are gutted, and once escaped into a stream or lake are virtually impossible to eradicate. Neither subzero temperatures, withering drought nor time itself can impact the viability of the spores, which simply wait out hardship for the chance at a free meal of fish head stew. The spores first must be eaten by their intermediate host, the tubifex worm, to alter form into a Triactinomyon, or TAM. Once released by the worm into the water, TAMs hook onto passing fish and burrow into the nervous system. Native to Europe, the disease first was detected in the United States in the 1950s and probably was carried to this continent with an importation of brown trout. Because brown trout evolved with whirling disease, they are more resistant but can be disease carriers.

Although other states have suffered serious losses due to the disease, New Mexico had no indications of the presence of whirling disease until this summer (2004). Bates’ investigation began at the ponds near Raton after he was alerted by Mike Sloane, an assistant chief of fisheries, that fish stocked in private ponds near Raton had come from a private hatchery in Colorado that recently tested positive.

Bates received permission from the landowner and his crew ran their nets in the ponds. “We sent the fish to a lab at Washington State University they came back positive,” Bates explains. “It was decided that we would do a complete eradication of these fish and it took us about three months.” But they couldn’t get them all.

“We knew how many were put in those ponds,” Bates said. “The numbers that we took out were roughly 70 to 80 percent of the fish that had been put in. Typically, there’s mortality associated with the stocking event and other mortality along the way.” The concern is that these infected ponds, despite their apparent isolation, ultimately feed into the Canadian River drainage.

And then the story took a turn for the worse.

Hatcheries Infected

As part of a routine hatchery check, Bates went out to get a “baseline” on any diseases that might be in New Mexico’s hatcheries.

“I took 20 of the ugliest fish I could find in each hatchery,” he said. “When Lisboa Springs and Seven Springs came back positive for whirling disease, we decided to take 60 fish from each lot.” A lot is a group of fish or fish eggs that comes from the same source at the same time.

Subsequent testing also found some fish at Parkview Hatchery infected with whirling disease, although Red River, Glenwood and Rock Lake all were determined to be free of the microspores. The Pecos River, Sloane said, is the most likely source of the contamination. Lisboa Springs Hatchery was using river water in some raceways and transfers of trout from those raceways to the Seven Springs and Parkview hatcheries appears to have spread the disease.

In response, an estimated 225,000 fish were destroyed. The action was in keeping with the Game and Fish Department’s interim whirling disease position which says the agency will not knowingly contribute to the spread of the disease. In addition, the Department intends to aggressively eradicate sources of the disease at state-run hatcheries and will continue to monitor the hatcheries for infestations. Plans for eliminating the source of contamination at Lisboa Springs could entail drilling wells and using more spring water rather than river water. A previously-scheduled $2 million renovation of Seven Springs is expected to resolve that hatchery’s problems.

Checking the streams and lakes which may have been stocked with potentially contaminated lots of rainbows, however, will take some time. Hatchery rainbows are stocked in a total of 173 New Mexico waters. Trout from the San Juan River, one of the state’s most popular trout fisheries, were found heavily infected. Anglers should clean their gear after fishing there in order to reduce the chance they will track it to other waters. Other waters will be tested following a prioritized list which recognizes the need to protect populations of native fish like Rio Grande cutthroat and Gila trout.

Anticipated Impacts

“One of the things we have going for us is that most of the waters in New Mexico don’t support wild reproduction of rainbows,” Sloane said.

Bates agreed. Many of the gravel creek bottoms rainbows need for spawning are above barriers intended to isolate rainbows from populations of native cutthroat. One option to reduce the impacts of the disease, which has the greatest impact on young fry less than two months old, is for the Department to stock older, larger fish. Caution will be necessary, however, because adult trout can be carriers of whirling disease and help spread it to those native species that do reproduce in the wild.

Fisheries supported entirely by hatchery stocking are not as seriously affected, according to Northeast Area Assistant Chief, Lief Ahlm. “The lasting and most devastating effects of whirling disease occur when the parasite is introduced to wild trout populations supported by natural reproduction it can cause the loss of entire year classes of young fish.”

Sloane said that “lots of habitat in New Mexico is not supportive of whirling disease. Most of our cold streams are fast-moving, and tubifex needs muddy backwater.” Since whirling disease requires both the fish and the worm to complete its life cycle, the role of tubifex is coming under increased scrutiny by researchers. Environmental variables, disease susceptibility in both hosts and timing factors are among the disease components being researched. Snake River cutthroat have shown a resistance to whirling disease, according to studies done by Colorado Division of Wildlife researcher Barry Nehring. He said that “[Colorado is] in the process of switching to Snake River cutthroats as an alternative to rainbow trout for a catchable product in [whirling disease-positive waters]. ” New Mexico currently stocks Snake River cutthroat in high mountain lakes in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

Research into the disease almost has become a business unto itself in Montana, where the legendary Madison River suffered a 90 percent drop in the rainbow population in 1994-thought to be largely a result of the disease. The Wild Trout Research Laboratory in Bozeman, Mont., is a state-of-the-art facility developed primarily for the study of whirling disease. The Whirling Disease Foundation, also in Bozeman, is a non-profit organization which funds extensive research on the disease and coordinates an annual symposium. Fisheries biologists agree it makes sense for New Mexico to tap into the information and resources of our neighbors to the north. As Bates says, “There’s no point in reinventing the wheel these other states have been dealing with this problem for years.” Representatives from Arizona, Colorado and the Turner Endangered Species Foundation of Montana were invited to a whirling disease working group that met for the first time in January in Raton.

Game and Fish biologists will certainly join forces with other agencies in order to maintain a viable trout fishery for the future of all New Mexicans.